Ought we not, from time to time, open ourselves

to cosmic sadness?

…

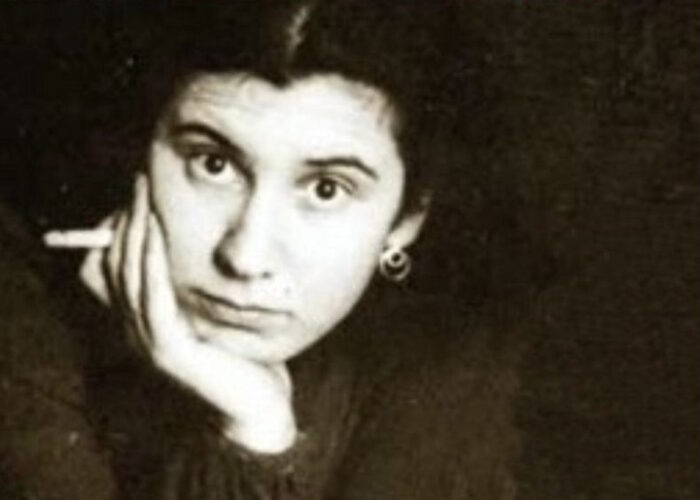

She was young, only 27, with faraway eyes,

clear, and penetrating.

A Dutch Jew, with something of the early Christian about her.

Yet neither conventionally Christian nor typically Jewish.

She followed her own spiritual rhythm,

not inspired by church or synagogue,

dogma or doctrine:

When I pray I hold a silly, naive or deadly serious dialogue

with what is deepest inside me, which for convenience’ sake,

I call God.

…

Give your sorrow

all the space and shelter in yourself that is its due.

Slowly, they removed her streets, her paths, her beloved stretches

of translucent sky, her trees—that bowed down under the weight

of the fruit of the stars—then her bicycle,

then her friends, then her family.

But if you do not build a decent shelter for your sorrow,

and instead reserve most of the space inside you for

hatred and thoughts of revenge—

from which new sorrows will be born for others—

then sorrow will never cease in this world

and will multiply.

When the train car pulled away from Westerbork,

toward Auschwitz, she flung out a note, later recovered:

The Lord is my high tower…

We left the camp singing…

…

I hate nobody, I am not embittered,

and once the love of mankind has germinated in you,

it will grow without measure.

…

Entering into Etty Hillesum’s diary is to step into

the evocative bodily fullness of life, to sink into the deep peace

between two breaths; into a deeper, radiant reality—

to taste of the way the world could be.

And if you have given the sorrow the space its gentle origins demand

then you may truly say,

life is beautiful and so rich, so beautiful and so rich

that it makes you want to believe in God.

…

This morning I am again thinking of Etty—how unsuited

she was to this world. How irreconcilable her soul,

how foreign her spirit is to the genocidal powers of this world.

At night, as I lay in the camp on my plank bed,

I was sometimes filled with an infinite tenderness and I prayed,

‘Let me be the thinking heart of these barracks.’

That is what I want to be.

The thinking heart of a whole concentration camp.

This thought is mine: how grieved—doubly grieved—

she would be, to see the Jewish nation-state, its current leaders,

this many years later, so efficient an oppressor.

Something else about this morning: the perception, very strongly borne in,

that despite all the suffering and injustice I cannot hate others.

All the appalling things that happen are no mysterious threats from afar,

but arise from fellow beings very close to us.

The terrifying thing is that systems grow too big for men

and hold them in a satanic grip,

the builders no less than the victims of the system,

much as large edifices and spires, created by men’s hands,

tower high above us, dominate us,

yet may collapse over our heads and bury us.

…

Many would call me an unrealistic fool

if they so much as suspected what I feel and think.

And yet there exists in me all the reality

the day can bring.

Where did it come from, her ability

to open herself to the cosmic sadness of the world—

such radical, undaunted empathy—

that allowed this kind of love to enter, grow, and stay with her?

And can a fraction happen in us?

…