As long as you read this poem

I will be writing it.

I am writing it here and now,

before your eyes…, —Alden Nowlan, “An Exchange of Gifts”

It sometimes happens that when a friend has died

and there is no funeral, no memorial, no farewell,

and the days pile in and routine has led you

to its temporary shelter; you find yourself

sitting down to an email, smiling about some incident

you need to share, and just before you click the address

you remember — and in the space of exactly one second,

memory flies you out over a horizon of clipped scenes,

walks you along a winding path of cropped stories,

and ends at a cliff overlooking a deep emptiness.

It sometimes happens while walking below those cliffs,

beneath the intertidal sky of grey hours,

between the froth and chop of collapsing waves

and looming walls of crumbling clay,

that a swallow swirls down, or a harbour seal comes,

swimming in currents roughly spiral,

adhering to a thing primal,

leaving no wake but curls of hurt,

and your soul, convinced by sorrow,

gives in to the gift of weeping.

It sometimes happens, then,

that you recall a poem by Alden Nowlan,

the one by your reading he is still writing,

as pledged, long after his death.

And in that flowering whorl of gifts exchanged,

obedient to the eddies of time,

you move toward the past, curving in ahead of you,

and from that spiral valence —

the known and unknown in full bloom —

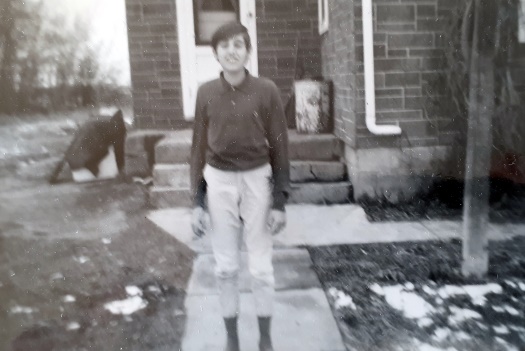

your friend: still walking in wonder

along a treed path by a river,

stops, waves a greeting, waves farewell.