As a kid, summer holidays at my cousins was like living in an episode of Darling Buds of May.

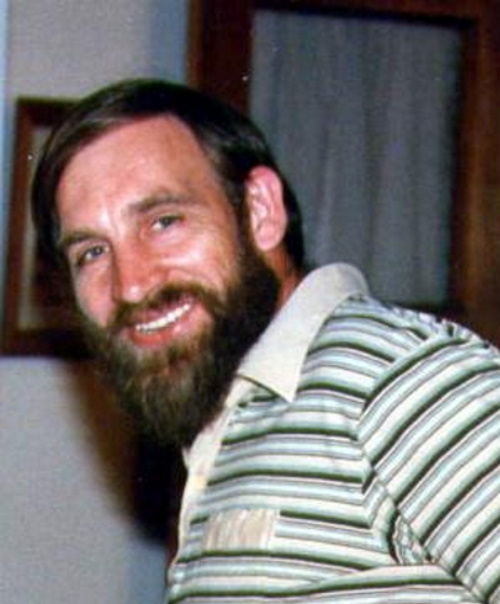

Jack (second eldest of nine) taught me the questionable joys of milking cows by hand.

How to drive cats mad, then satisfy, with a wavering stream of hot milk straight from the teat.

Showed me, although I’d never have the knack, how to strip down an old “junker”, get its last mile, fly up a river hill flat out, spin ‘till the engine choked, ease down without rolling.

Taught me what it meant to stack green hay bales until your muscles were hard and your back brown from the sun.

Showed me how to spit and split wood.

How to get dyed yellow and scratched bloody from rogueing wild mustard and Canada thistle in a 40-acre oat field.

How to swim in a muddy river, or swim out beyond a lake shore smothered by algae.

How to go through a chunk of summer without shoes.

How to snare a weasel, skin a beaver, things that didn’t take, but fascinated me because Jack — tireless, tumble-down-a-hill, fleshed-out-Huck-Finn — did them.

I was there when he played the clown at an auction sale: walking into machinery, rolling in the grass, making me roll with laughter. Finally told to stop because the auctioneer couldn’t keep the crowd.

He had cracked-clay, hardpan patches in his life. He gave up much, lost more.

At times, he was taken advantage of, responded without retribution.

Had that kind of heart.

Had that kind of uncluttered, unencumbered faith.

He never thought to make a mark.

Never concerned himself with grand schemes.

Was not sophisticated. Fact is, he scoffed at sophistication. Not with words,

but by quietly living without our culture’s blinding self-consciousness and preening competitiveness.

It was Paul Ricoeur who wrote about a second naiveté, a spiritual progression from face-value thinking, through critical reflection, to a kind of reengaged innocence.

But Ricoeur didn’t know Jack. Jack was born to it. For him, all three were one in the same.

Which made him a giving person. The kind Jesus was thinking of when he coined, “salt of the earth.”

One winter morning after a Saskatchewan snowstorm; radio warned of impassible roads. But there were chores that needed doing. My dad was cautious, said, “Chickens can wait for the snow plow.” But Jack had no qualms. And I was up for the ride.

The farm was four miles from town. We made it three. Smacked through a dozen drifts, hard white waves hitting the hull of the one-ton Ford. Jack, hammering the gas pedal between drifts, but we were slowing with each one, the snow coming higher, flying over the windshield.

The last drift was mean. High and crusted hard. Stopped us like a nail hitting a knot. Killed the engine. Jack looked surprised. Jumped out, started shovelling. Steel grain shovel arching, swinging with rockabilly rhythm and I thought the truck might start moving on its own.

I tried to help. Pulled snow from around the engine. Jack worked the packed blizzard out from under the body, axles, then made a trail through the drifts ahead.

Under the crystals hanging in the distance, he was a dervish blur of snow and steam. I stood watching, freezing in the minus 30, arms hanging, hands going numb, thumbs folded in palms inside my leather mitts.

Jack was back at the truck, grinning, “Lets give her a go.” Then noticed, said, “Your freezing, give me your hands.”

He took them both into his. And we stood there, in front of the truck grille. His hands hot, radiating, thawing mine.

The truck kicked to life.

He rocked it back and forth. Took a few runs and broke free.

And that’s just how he lived.

And I’m guessing, how he died.

The last time I talked to Jack (too long ago), I asked him how he was doing. He said, “If I was any happier they’d have to put me away.”

Jack’s affluence was life. Because of that, today, the world proper, is a little poorer.