“Everything has a pulse,” he says.

We’re having coffee, sitting in a small alcove high above

Finlayson Arm, that lurid-blue limb of sea

that narrows toward Gold Stream.

Below us, down a broad path, a recently built lookout tower

is being readied for those who want the encompassing view.

“There are connecting points everywhere,” he says.

I watch his mind at work, he’s traversing the paths

of a lifelong preoccupation. “How would it be if humanity

could rest together, in an open-minded, open-hearted,

condition of presence?

What if our hearts, our bodies, our selves, were in sync

with the rhythm of earth, the universe itself?”

It’s a conversation, even at this dizzy elevation, that feels natural

because of his many years of immersion.

Then we talk about the rabbit that breached his garden fence,

his water catchment system, his modifications of a winch

and wagon to haul dead-fall out of his back acres,

his many lively inventions.

I could listen to him at length,

but always, he asks about me.

Later, he says,

“The thing to do is to have the experience, to see that it’s possible.”

He’s reconfigured a biofeedback device:

four sit in a circle, connected by leads to monitors.

Screens display the independent beats of their hearts.

They fall silent.

Soon their waves will rhyme.

Many years ago, to further his search,

he built a float tank, the first of its kind on the coast.

(Later spawning float tank centres.)

You step in, close the lid and lie in warm, salt-steeped water.

Your body, fully suspended—freed of all conditioned senses.

In darkness and naked silence, you detach—released

to a preconscious, circadian calm.

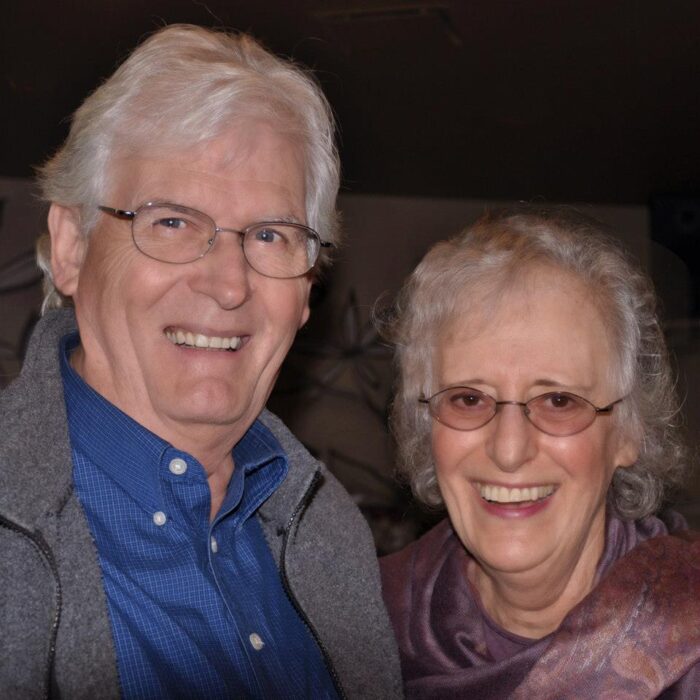

He lives with a poet, herself, a believer in pulse and harmony,

who knows intimately that the heart is a great muscle,

that starves like a winter raven for connection,

and thrives when surrounded by leaf and bloom,

and friends with whom to share

yam-almond soup.

Yesterday, the sun casually warming the glassed-in veranda,

Rod spoke of their early times together. “Right here,

where we’re sitting, 25-years-ago or so; I was Wendy’s

chosen audience, and she read her poems to me,

as naturally as breathing,

and O,” the words catch in his throat, “she just killed me.”

Today, mesothelioma, will not release him. Years,

working in oblivious mills,

indiscriminate asbestos

filling his lungs with micron-sized fishhooks.

He fights for life, lives with acceptance.

Puts things in order and hopes for time.

We visit, or call, and talk of the amount of rain,

the whitecaps on Juan de Fuca, the squalls of pain

surrounding his lungs, the potholes of medications,

the sorrow of endings, the joy that’s leaked out

of his model train room, and then, a lighter moment,

a laugh before good-bye. And I

see clearer how I should view my own time.

He lives in a house where the ocean is the horizon,

the forest looms behind, trails he’s cut lead up to a lookout.

And sloping west, there’s a garden, where fruit trees his age

bloom in any weather, and everywhere

and always, there’s a pulse.