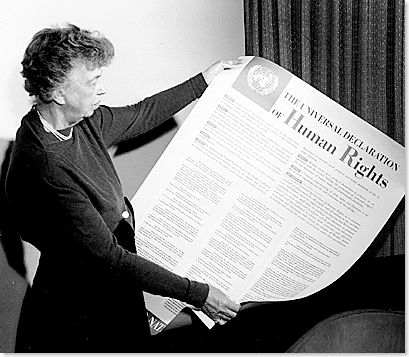

In 1947 when Eleanor Roosevelt convened the first international counsel that would later produce the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it was thought that the implementation of rights would flow from the moral and political force of the document itself. After all, the waste and carnage of two global wars had so wearied the soul of the planet that there was an earnest gut-desire to enter a new era of peace, a "world made new."

Those were heady days. Even as the cold war loomed, there was optimism that the UN, wielding the ethical force of the UDHR–signed by 48 nations, with only 8 abstentions–would be able to convince all nations, even tyrannical nations, to uphold the right to life, liberty and security, of all individuals, regardless of race or religion, colour or creed, political opinion or social origin.

Eleanor would be gravely depressed. The last half of the 20 century has seen countless human rights violations, even by many of the signatories–and especially by the most powerful of signatory. And while over 1000 NGO’s sprung up to monitor human rights implementation, this did little to shame any nation into line.

Today, the Human Rights regime is in apparent crisis. And globalization, instead of drawing us closer, is seemingly splintering nations further. Add to that the current economic pressure and the protectionist bent of every nation and tribe, and the world seems poised for more rounds of violence and human rights abuses.

Does it mean that the UDHR and its attempted application wasn’t worth the effort? Not at all. The UDHR stands as a magna carta of sorts and has no doubt forestalled much entrenched conflict.

But there is a also a core difficulty. If the maintenance of human rights can’t rely on political and moral force what can it rely on? If it relies on physical force it undermines it’s own articles–its own foundation and hope.

So while the declaration is important and needed, it is highly provisional, culturally relative, and forever flawed, because it not only misreads the mimetic nature of violence, but also, because it is "methodologically atheistic." That is, at the point where the UDHR introduces values such as the "innate dignity of humans" it chooses to ground these values in a belief in human moral progress. What I mean is that it tries to stay metaphysically free. But because this is an impossibility it deludes itself and remains tied to the rationality of the Enlightenment, the rationality that lead, in part, to the wars of the 20 century, which then lead to the formation of the UDHR. (For an eloquent and eminently reasoned opposition to my understanding, read Michael Ignatieff’s, Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry.)

So, while the UDHR is still in some way a necessary and humanizing document, it cannot of itself, as was hoped, create a cooperative and peaceful world. Only through a deep understanding of our own propensity for violence, sacrifice and scapegoating, can a trajectory of hope for peace be sustained. As for me, I have found no other narrative other than the gospel, that opens up the possibility of a culture of peace. That’s because it lifts the mask of our innate propensity to first find fault in another.