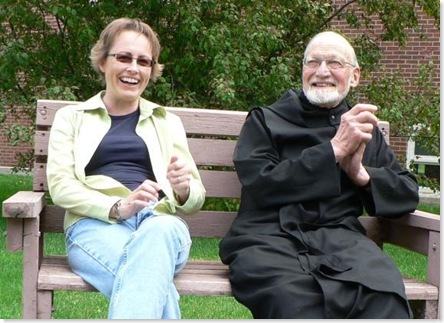

A couple weeks ago, the last time we had tea with James, he dropped his cup–the lip broke on the floor and tea splashed over the tile. The three of us, Deb and I, and Fr. James in his habit, got down on our knees and cleaned everything up with Kleenex. He joked that he’d better leave before he wrecked the place. We talked some more and then he left, but not before giving us one of his vice-grip hugs.

A few days ago, while visiting him in the hospital he began to wonder about the stuff of his life. Knowing I wouldn’t see him again, I failingly tried to express my gratitude for his friendship. He said he hoped that his life made a difference. I told him that it made a difference to me. I told him that just having tea with him made a difference. He said he supposed everything we did was ministry. After this, he began slipping in and out. Then, Easter Monday, he died.

I felt uniquely special in his life, but I also know that others felt the same way. That was part of his gift.

Souls contact and change the motion and direction of other souls. It’s biological-billiards. Father James was one soul who changed my trajectory.

Souls also mingle and change each others structures. Father James was someone who mixed with and influenced people the way lime influences acidic soil, or the way loam effects gumbo. He mixed with people and improved their tilth.

Any death is hard to bear. We try to stand up under its weight. The weight is there, but it helps to know that Fr. James already saw his death as release. He was ready for it and although he wouldn’t say he welcomed it, there was, in him, no resentment or fear of death at all.

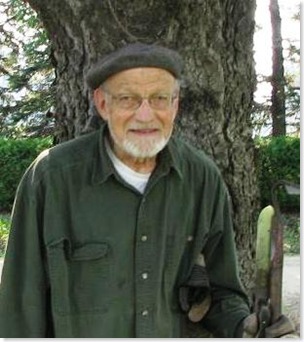

Even before the trouble with his aorta, we often talked about death. It’s a Benedictine thing. In fact as a monk he would have been used to contemplating death daily. The Rule of St. Benedict counsels it. Whether that is really possible, who knows. To our sensibilities, considering death appears morbid. But recalling our mortality, for Benedictines, is a way of cultivating compassion for life. In this, there is nothing of the evasive busyness, the infatuation with youthfulness, the false security, we moderns comfort ourselves with. Making room for death is basic balanced reality.

Life is delicate, remembering our mortality helps us treat life gently. Recalling that we mortals are all in this together will help us treat each other with kindness. And in some way, when we treat each other with tenderness, we are already living as though death is behind us.

Life is delicate, remembering our mortality helps us treat life gently. Recalling that we mortals are all in this together will help us treat each other with kindness. And in some way, when we treat each other with tenderness, we are already living as though death is behind us.

Fr. James’ life came rising and shining into this world–and when it set, at least one corner of the world was found a better place.