I sit in a café in the early hours.

I have no agenda, no manifesto, no religion that needs defending.

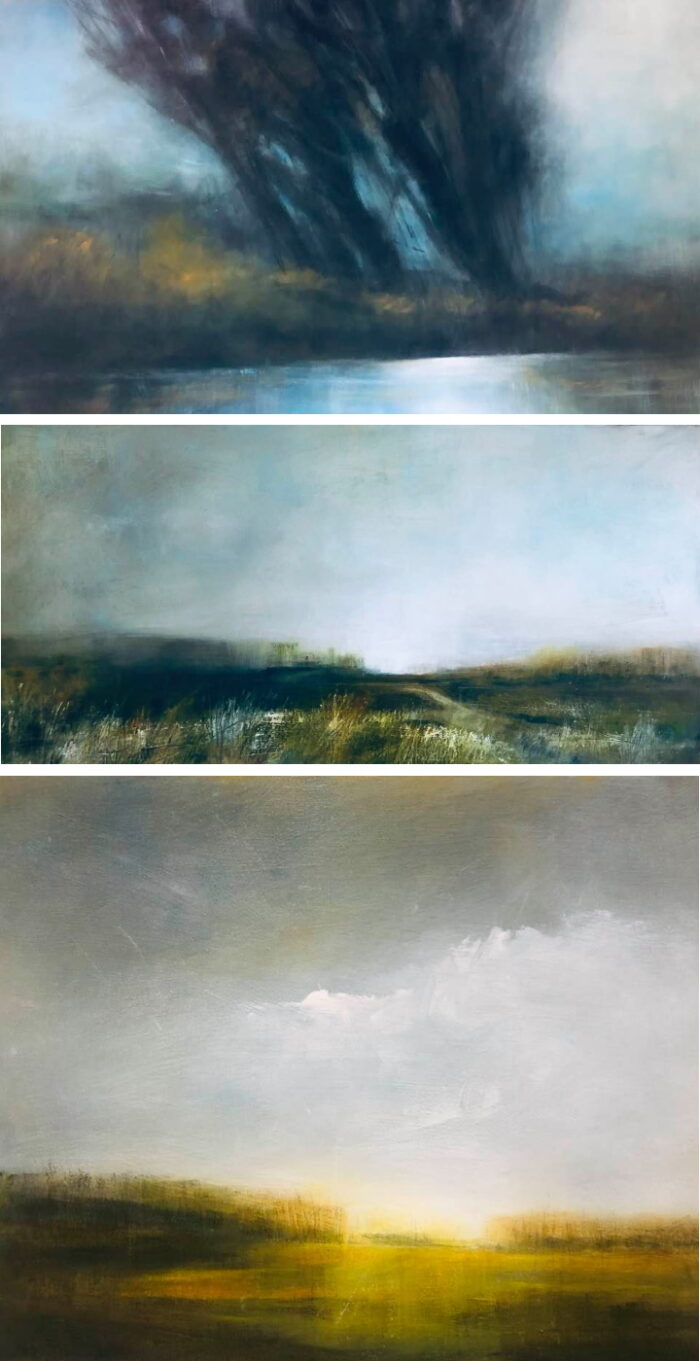

The morning sky is tangerine and tousled by clouds.

People are friendly.

No one has come here with that quote by Sartre.

No one is reading the principles of Sun Tzu.

Little Wing is playing through the overhead speakers.

Hints of frost on the large eastern window.

I’m warm in my Merino.

It’s February on the island. Snowdrops are up.

At a table beside me there’s a woman who is beautiful and plain.

I see the eyes of my mother — then I hear the voice of my father.

The woman glances up over her coffee, toward her partner,

a dark strand of hair, like a rush of love, falls across her cheek.

My memories are strands of wool, dropped and scattered over the earth.

I sit. Voices around me, like blessed water running over polished rock.

At a table near the back, I hear the glad cries of my sisters and brothers.

They are playing Rook, past midnight.

They are in me like piers in a port.

A trans woman enters who has the face of the Black Madonna.

Behind her, a mother, with a daughter whose midriff is exposed

and pierced with a jewel.

An old man in a wheelchair is sitting alone, with news.

A waiter is clearing and wiping a table and speaking softly

to a child, using the language of a child.

The nation’s flag is sewn on the brown jacket of a young man,

waiting for his Americano.

A business person, wearing straight lines and severe lipstick,

is waiting for some form of kindness.

An angel stands outside with his shopping cart and paper cup.

All of us here, like salt in a sea.

One in all, like coral; all in one, like the bride of Christ.

Before there were fists, there were open palms.

Even a gun was once an oak, and ore, gleaming from a cliff.

Tears of happiness well up in me,

the way brooks form on mountains after a day of rain,

the way a drop of love gathers more love.

Afterward, my eyes dry, I sit before my table.

It is built low and circular, like a bay prepared for boats

in some divine unfolding dream.