Two years ago I wrote a review of this book. I sent it to a couple places, one asked me to shorten it. I didn’t want to. I don’t recall hearing back from the other (there are of course other good reviews out there). Because I can be lazy, and because life goes on, I shelved it. Well, as you know, life has hit the brakes for us all and is telling us, Go back, rekindle things you love. So I remembered this book (the relevance of which seems especially apt today). Here’s the review:

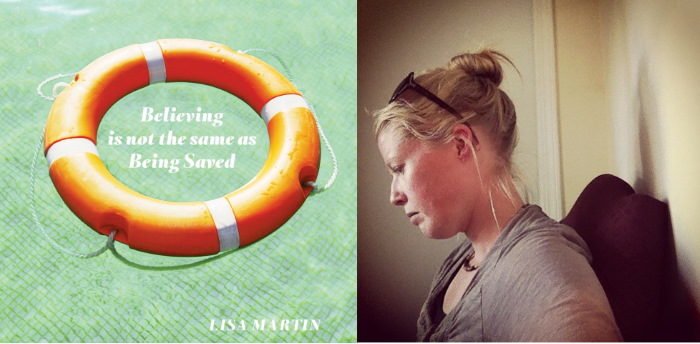

Believing is not the same as Being Saved — Lisa Martin

Growing up in a Baptist church, where evangelical dogma was as incontrovertible as the prairie sky streaming in through lancet windows, hardly a Sunday went by when I wasn’t reminded of the verse: “Believe in the Lord Jesus Christ and thou shalt be saved.” This verse, found in that crackling Book of Acts, shaped me, gave me parameters for a special sort of belonging above the lost world around me. Of course, that simplistic and misshapen template has been overlaid by seasons of experience, and I hope, some wisdom and grace; and yet, like invisible ink under certain light, it reappears. So when I saw a book of poetry called, Believing is not the same as Being Saved (2017), how could I avoid being intrigued?

Several readings later I’ve come to regard this book as root-and-branch inspired. For beyond the seemingly effortless marriages of meaning and meter, rhythm and reality, imagery and emotion; beyond the simple elegance of Martin’s language, the fluid lyricism, the fresh and surprising images, lies a soulful might and a germinating and generous faith that holds you, walks you through the complexities of grief, suffering, loss, and the flawed, incomplete natures of joy and love.

While this mosaic of 58 poems consists primarily of narratives, with a few crisp epigrams and evolved sonnets to punctuate, the narrative structure, whether in prose or metrical form, never feels secondary—something on which to hang images, metaphors. Rather, the internal mode of narrative feels essential, natural to the “story.”

There is a deeply personal story here, but it is not sticky with personality, nor is it autobiographically bulky or confessional in any therapeutic sense. Instead, the figure behind these poems is present in a lambent way, allowing for a broad memory, specifically, a frayed and haunting Judaeo-Christian memory.

As it is, almost every poem transmits the presence of a mind in search of a new form of faith, the presence of a questioning heart undergoing some form of transformation. Most of these poems could qualify as meditations of a modern pilgrim—uneasy with anything like prescription, changelessness, immutability.

… Even now, what I want most

isn’t to walk past that song into knowledge.

Believe me: I want to sing, despite

everything. I want to believe

we all could be saved.

But nothing is assured. In this, the book’s eponymous poem, we encounter the accidental death of a teenage girl, at what was, although not stated, most likely a conservative Christian summer camp. Martin’s response to the death, deeply felt and broodingly attended to, sets her on a path of penetrating reflection, and ultimately, transformation.

I flicked off a switch that summer

as I walked. I wanted to understand

darkness, the quality of my heart: not light

but spark. …

Here it seems, is a key to the book. How can we live with integrity in the grip of life’s contingencies? How can we build an authentic life in the face of life’s self-contradictions? How can we be devotees of life in the ever-present shadow of death? Answer: Not by waiting for revelation, not by resting on the framework of doctrine, only, it seems, by plunging into the dark of one’s own heart, in the paradoxical hope that in the absence of light, any small glimmer, even in the unlikeliest of places, will be noticed. Here, from “Incandescent Light:”

Yet, beneath the threshold of visible light

where things go—underground—to dieand survive there is a bountiful glow,

inefficient as love itself, produced by all

this decomposition. …

Light, love, through decomposition? The discovery here is not the insufficiency of love and longing, but its inefficiency, it’s consuming fragility, its dim fragmented focus.

…The spirit is a lonely

filament. It longs—as the body longs—

for heat. To burn, and not be consumed.

You scrawl someone’s name on the wall.

You are so alive it hurts now—

struck, match-like, by what you love,

incandescent as home. You want this world

& your unrequited love & God at last

to speak the same language. Even if that

means you lie down in the dark, alone.

Pulled past limits afforded by light, these are poems that have found their form in the womb of darkness. Martin has taken to heart Amiri Baraka’s belief that the weights of experience have got to drag whoever’s writing in a personally sanctified direction or there will be no poems at all.

Ten years in the making, this work is an enduring testament of “personally sanctified” survival. Surviving the death of both parents, the end of a marriage, and surviving, if not a moribund faith (“Faith had calved like a doomed glacier” – “Ecstasis”), certainly a dysplastic faith.

“To survive we migrate,” writes Martin. However, her talent is not to function as travel guide, but to live before us, to stretch toward the unsayable and make accessible, therefore survivable, the deep registers of grief. This kind of grief, according to Seamus Heaney, “had better not be shut off…is something poetry has to take cognizance of.” The pith of this book is just this sort of cognizance. It is grief undergone and given form. Consider, “Sonnet to myself and a stranger:”

If I could know you by telemetry,

or other remote measure, could I solve

the mute unanswerable sorrow at

this world’s dark heart? No. Proximity is

the only art. …

The tourist life, while emotionally comfortable, is not life—the self remains a stranger. One gets the sense that what is being worked out in these poems is just this art of proximity. That is, finding the personal axis mundi favourable for flourishing. However, we are reminded again that the apprenticeship for proximity comes only by sinking into this “world’s dark heart.” The poem “Separated,” likewise observes: “be alive to pain” as it may be “a form of intelligence / a tool.”

Martin’s “form of intelligence” is akin to what Keats, now famously, coined as negative capability. That is, the ability of setting aside self-consciousness and opening oneself to the event or object contemplated, and dwelling comfortably in its inevitable mystery. Here: “Its path marks the place where the mind gives up / on what it knows (Map for the road home).” Or here, “Faith and doubt—like evaporation and condensation. Each occurs at the other’s / threshold (The Ascension).”

In the ironically titled “Lightening up,” Martin writes:

…what is the nature of

being human we are prone to asking? Sometimes

implication precedes understanding, but the latter

does not always follow.

This is an anthropological question, but it’s also a religious question. It’s worth noting that Believing is not the same as Being Saved appears at a time when the church is hollowing out, when much of Christianity is wandering in a wilderness of its own making; not the least of which is its historical antagonism toward uncertainty. And yet, and because of this, it is a time when the questions of who we are and how to live haunt us as never before.

If the problem with fundamentalism is that it starts with the absolute authoritative word and therefore invariably produces a bifurcated experience; and if the problem with rationalistic atheism (home for many lapsed fundamentalists) is that it fails to account for mystery that is everywhere present in this buzzing and blooming multiverse, then Martin’s book gives one a place to stand. For it lives somewhere between and beyond these “faiths.” It lives in the pulp and juice of human experience, it plays in a field of opposites, of enigma and paradox, in the tortured radiance that takes full account our inescapable contingency, without slipping into the casual nihilism of our day.

Personally, on this point, while this book exposes the vacuity of rigid structures of faith—such as the faith of my upbringing, I found myself mysteriously re-engaged by faith.

This poetic intelligence, this keen inner-eye with its ability to create a quilt of reality out of paradox and mystery, and a path through the halting confusions of grief and loss, is both gift and achievement.

In addition, for all the difficult poems, the sorrow, the loss, there are verses and whole poems that come as shafts of pure joy, shining twice as bright as a result. Consider “Biology,” a poem that reads like an antiphonal response to A.R. Ammons’, “The City Limits:”

… Let us buzz together with fractious

indelicate joy; let us go all the way through with it

as dragonflies do in the bright blue returning

of summer’s need, heat, together again

in the chaos of belonging to everything, fully

so that anything or anyone among us by

touching or not touching might transform

us, what we are at the quick.

This is a work that touches the quick, holds the heart. “Stories are for transforming ourselves,” states the title of another of Martin’s poems. In the story that percolates and finally spills outside the covers of this book, I find myself somehow transformed.

You’ll find this book and others here on Lisa Martin’s website.

Wow Stephen. I do love you. I get so much of this beautifully written review having a independently forged and hopefully personally sanctified faith. The poetry is sublime and the way you’ve reviewed it is pure poetry. Lisa

Thank you so much Ana Lisa! You are gracious and generous.

Thanks, Steve!

An insightful, affirming review and reflection, highlighting our call to a way of ‘Being’/becoming versus a mere way of ‘believing’ !

Thanks Ike! And yes, to “our call to a way of Being,” well put!