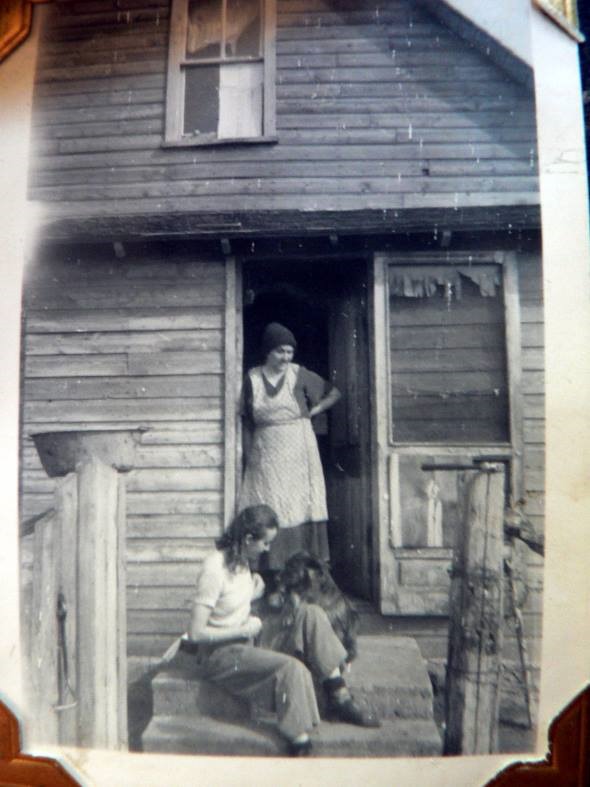

My grandmother, standing at the door, my mother enjoying a break from chores. (1930’s)

This is a slightly revised version of a piece that was published in the Edmonton Journal (Religion) about eight years ago.

The school bus drops me off at the farm gate. As I approach our house the smell of warm bread comes to me through the screen door. I forget myself and drop my books in the porch—a habit I’m to break.

In the kitchen close to a dozen loaves of white bread are lined up cooling on the counter. One loaf is set apart. Beside it is a large square of butter on a saucer and beside that, a cereal bowl full of raspberry jam. All this is for me and my sister and our foster brothers.

We cut thick slices, and with flattened chunks of butter still melting underneath hills of jam, we eat wearing broad smiles.

It’s a gilded Leave it to Beaver memory. And although it’s one that warms me, it’s not the whole picture, and not the one my mother carries.

My mother made bread every week. I remember watching her one day. As she leaned over a square twenty-gallon galvanized tub punching down bread dough, some of her hair had come loose from the comb fastened at the back of her head and damp strands hung down past her face. I watched her body strain and her face tighten as she punched down the dough with her fists.

Until that day all I knew was that a dozen steaming loaves would come out of the oven at more or less the same time each week. It came as a revelation to me that making bread was hard work.

I never knew the meaning of “give us our daily bread” the way my mother knew it.

I take bread, and most everything it references, for granted. The concept of not being guaranteed daily provision seems an unreal thing to me.

For my mother however, making bread, not buying it, was a necessity. It’s been a slow dawning, but I know now that my mother had, and still has, a keener sense of daily dependence than I. She wasn’t looking for a deeper reality through the bite of hard times. It just happened. And she chose to understand life’s contingencies through her hands, too early arthritic.

The concept—‘poverty of spirit’—has a catalogue of great minds and tomes of text devoted to its exposition, but all that is a bit of fluff beside an embodied humility that receives with gratitude and takes little in life for granted.

The concept—‘poverty of spirit’—has a catalogue of great minds and tomes of text devoted to its exposition, but all that is a bit of fluff beside an embodied humility that receives with gratitude and takes little in life for granted.

My mother knew that Jesus had called himself the “bread of heaven.” She had a picture with a verse to that effect, hanging in the kitchen.

This reference, for mom, had, and still has, a wide meaning. She believes that Jesus satisfies all inner and outer needs. This is a naïveté that gets dismissed readily—and often deserves to be—if not formed within a kind of “existential verification.” That is to say, I see my mother’s naïveté as a living articulation of something she would not herself attempt to preach.

But in all of this I can’t help but think that my mother, through a kind of unconscious exchange, through her connection with Jesus as “bread of heaven,” became for me and our family, a form of Eucharist. With her fists buried deep in a hundred essential tasks, her heart navigating the rocky and changing channel between concern and control, acceptance and censure, she became broken for her children.

But in this she is like mothers everywhere. What mother, in some way, has not been broken for her children? What mother has not known the dark midnight of worry—in pregnancy, in her child’s childhood, in her child’s adulthood? And what mother has not spent herself, and would not endlessly spend herself, for her child’s safe passage?

There has never been an easy epoch in which to be a mother. How motherhood is received, learned, and carried out, is, for each mother, a uniquely layered story. But what is universally shared by mothers, even incompetent mothers, is the pull to nurture. And in this pull, most mothers, unseen and unheralded, become, like my own mother, a scattering of broken bread for the long blessing of their children.

As beautiful and true as it was the first time I read it, back then.

This is a wonderful piece.

Stephen, this is such a lovely, but poignant piece. The “pull of nurture” is something I understand now, only after being a mother myself. And I think that these words of yours help me to understand my mother – with whom I have a complex relationship – a bit better.

The picture of your grandmother’s house – complete with the screen door, concrete steps and dog – remind me so much of the old farmhouse where my mother grew up and my grandmother lived until her 80’s (woodstove, outhouse, 1 cold water faucet)…

Thank you Connie and Theresa. I am blessed by your comments.

Thank you Diane. It makes me glad that the writing can in some small way work understanding. I’ve been spending time looking at old photographs. Wondering, believing, that they will reveal all that the moment possesses. But it’s a long discipline, a way of seeing. Thanks again for your response.

again… beautiful Steve. My heart melts just like the butter.

see you soon

In the January 14, 2012 Edmonton Journal, you listed a proposition that you believed but can’t prove: “…that words, as Elie Wiesel says, in moments of grace can attain the quality of deeds.” Well Mother’s Day-Daily Bread reached out and touched me in a moment of grace. Thanks, and from my experience your proposition has been proven!

Ah…thank you Joanne!

Thank you so much Raymond. Such a lovely response. And thank you for reminding me of this quote. Words I adopted years ago, but I still need reminding.