I used to know little of still life. Now, having read Shawna Lemay’s Calm Things, which is essentially a meditative study on still life, somehow, I know even less.

I have, however, learned some things: for instance, I’ve learned that the term still life, what the Japanese refer to as calm things, didn’t come into being until 1650. But then, considering art such as the frescos at Pompeii, “still life” has been getting on for at least a couple thousand years without a designation.

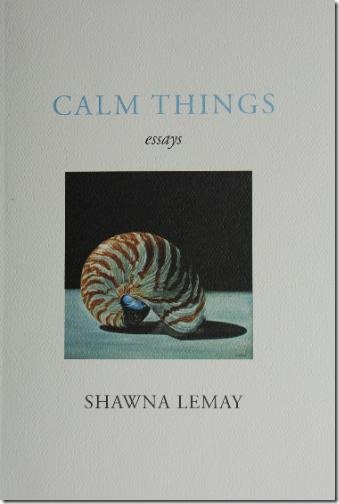

I’ve also been introduced to painters: Claesz, Kalf, Vermeer, Morandi, Zurburan, as well as Shawna Lemay’s husband, Robert. Some paint plums with such concentration that they can be tasted, paint sea shells with such attentiveness, they can be listened through. And some paint with a kind of watchful patience that seem to induce objects to approach, to leave behind their detailed objectiveness, to become spaces of relative thermal radiance.

I’ve also been introduced to painters: Claesz, Kalf, Vermeer, Morandi, Zurburan, as well as Shawna Lemay’s husband, Robert. Some paint plums with such concentration that they can be tasted, paint sea shells with such attentiveness, they can be listened through. And some paint with a kind of watchful patience that seem to induce objects to approach, to leave behind their detailed objectiveness, to become spaces of relative thermal radiance.

It’s this kind of attentiveness that Calm Things is about. But it’s more than a book about still life. Woven through these essays are one poet’s perspectives and insights about the writing life; about the lives and habits of artist’s; about the colours of life, the strokes of doubt, the shades of confidence, the backgrounds of loss and delight…all the stuff involved in the laborious and precarious walk of moving toward a calling; becoming what you are.

Too, this is a thoroughly human book touching on marriage, family, neighbourhood, on love, defeat, reverence…and all placed on the page with tonal eloquence. These are essays, but they can be savoured as long-form poems.

Towards the end of the book, in an essay matchlessly titled, Of Coffee Pots, Teacups, Asparagus and the Like, I found two sentences that, while describing the gift of a bit of light in a still life scene, could just as easily describe this book, as well as stand in as a mission statement for most artists:

“Beautiful and whole in itself, bare and simple and yet radiant with an inner life that seems to emanate from the bowl, this gift reminds me to carry on putting forward those things I can write, however small or sidelong they may seem. To develop a generosity from deep within so that it can erupt, thereby enlightening the soul, and even infect the souls of others with a similar generosity.”

It would make sense to leave off here and just say that this is a wondrous and somehow timeless book. But I’ve become hooked on still life, well, maybe it’s a fling, whatever, I’ve been drawn in. But I struggle to put words to what it is that’s pulling me, or what’s been added. I’m not unacquainted with certain notions validated by still life. Notions such as the power of simplicity, the majestic in the domestic, the imperative of dwelling in silence within the earthed feel of a single moment; these come by simply looking at a painting, attending to the objects, the arrangement, the background, the light and shadow.

But scouting around for the past while, even in the poverty of digital reproductions, a mere question has come: what else is here? I seem to be asked for a deeper response of which I’m incapable of. I look at, say, a Zurburan, and know that I’m in the vicinity of a liminal event, on the threshold of a dark quiet passage and all I can do is gaze. I see soon enough that I’m dealing with powerful elements here…an orange, a lemon, a cup, a petal, a peel, all Blake’s angels, all rumoured conduits for a particular form of immanence.

There may be those who are able to use these paintings as staging arenas for deep meaning, I take them to be clouds of unknowing. But as the author notes, quoting Norman Bryson, still life is “outside narrative.” So in this sense, it is a language of its own; therefore what is said, can only be said by it and through it.

And yet, foolishly, I want to say something about these clouds. Certainly I’m beyond my ken, in reaches too lofty for me; so I will borrow the reins of Martin Buber and say that still life may be a kind of apprenticeship for moving toward your “I.” As it’s only an “I” that is able to truly say “Thou.” And, paradoxically, it’s only within this found inter-dependence can we understand the organism we. The immanence and transcendence we long for.

But perhaps all good art—not still life alone—is clarifying. If only to behold and say, I’m at my limit, but there’s more. Clarifying: in the Socratic sense of discovering, yet again, that we know less than we think, even as our bodies-and-souls know more than they can say.

Shawna Lemay blogs at Calm Things

Beautiful, Steve. If I may paraphrase, the eternal “I AM” greets the finite, created and drives out all fear with a perfect love.

Thank you Sam.