Here’s the conclusion to (last month’s) ‘In the name of Love’ post. But for continuity, I’ve posted the entire essay.

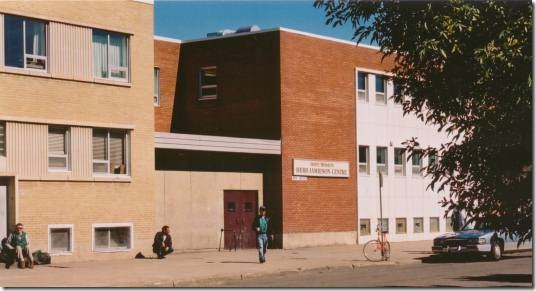

Years ago an unimportant and diffident man was giving a tour of a homeless shelter—of which he was manager. Requests for tours were not overly frequent and they could be pleasant, and the guests were often interesting—which always made the man question his own credibility and worth. Still, his tendency toward introversion and his perpetual hope for a day on his own terms often caused him to feel ambivalent about the whole enterprise.

On this particular occasion, as he was walking down the hall leading his guests through the shelter’s medical dorms, explaining, as he always did, the dimensions of the work, the problems of poverty and mental illness and addictions and abuse associated with those living in the dorms, Mr. Fond came shuffling down the hall. As usual his pants were gathered at the front, held up by and one clutching arthritic fist, and his shoes were loose with laces dragging. For a moment Mr. Fond’s eyes searched the tour guide’s eyes—who knew what was wanted. But time taken to lace up his shoes would be a waste; he would soon have them untied, sloppy-loose and would return to shuffling. And so the tour-leader, who was conscious of appearance and wary of spectacle, and able to define the nuances between the two, resolved to smile, greet Mr. Fond, and politely yet efficiently continue his tour without interruption.

But as these two minor bodies closed distance, our man of moral lassitude was nevertheless unable to pass by. And so he stopped. And as he knelt before Mr. Fond, catching the miasma of blotched and liniment-chafed flesh; and as he raised the crusted cuffs of the pants, taking the flat-frayed and soiled laces in his hands, crossing and looping the ends into a double knot; and while feeling the sting of embarrassment from what he thought must be the indulgent glances of the dignitaries standing off to the side, he felt within his solar-plexus a small warm growing thing. It was like a malleable ball of desire deep in the centre of his nervous system that continually changed shape from Mr. Fond, to himself, to the well-appointed noblesse, and back again.

Now he liked this—himself-but-not-exactly-himself—feeling, and being the selfish sort he wondered how to keep it, own it perhaps; this “it” that now, sitting back at his desk and staring into the glass-brick window, still felt sweet and pleasant, like mulled wine pooling at the pit of his stomach.

And as he stared, seeing dimly through the clouded glass, thinking he saw that bright yellow ball of desire—within or without he didn’t know—his teetering mind fell to reflect upon the occurrences carried out daily by heart-filled workers and volunteers at shelters and hospices and homes and streets around the world—habits of millions of ordinary humans. And he opened to the thought that this “it” was the natural renewable waiting-to-be-discovered desire at the centre of every-body and so could hardly be something kept, held or owned, but was always moving, shifting and weaving. Always and everywhere stopping and stooping and kneeling in the name of Jesus, in the name of Allah, in the name of Nothingness, in the name of human kindness, in the name of the Creator, in the name of Kookoomis Manitou Muskwa, in the name of the one Spirit, which is of one genus, which is love.

And in an unaccustomed flight of imagination he somehow knew that these were all minor miracles that kept the rotation of the earth within its critical and delicate tolerances and he saw how these fertile bulbs of desire covered and balanced the world.

He remembered now how Jesus, a law breaker, had called himself the fulfilment of the law. And how his apostle come interpreter Paul, had perfectly nut-shelled it when he wrote that there is simply no law against love and things like peace, kindness, generosity and gentleness. And that those who are operating within the order of love are already beyond the law, not subject to the law; not subject to parsing out us and them, or assessing who’s in or who’s out. Those who love, are the liberated, the truly law-less.

And he saw how his own envy and group-think and petty-piety had kept him blind to the possibilities of grand inclusion; he saw how his apparent need to shield and own the "it" and use it as one more differentiation for his oft-bolstered fence was what too much of religion is about. And yet he thought, how expansive love is that even with this law abiding, or rather, binding intent, the "it" is not entirely cooled in relation. At least not immediately.

And he also saw, perhaps by virtue of his first seeing, into the sometimes merely confused and other times calculated obfuscation of a double-bind Christianity. How a fawning, "the women, God bless ‘em" was a way to woman-proof the church; and how love-the-sinner-hate-the-sin was used to gay-proof the church, and God-so-loved-the-whole-world could nevertheless ignore the neighbour; and how go-throughout-the-world-and-preach-the-gospel had been used as moral justification for colonialism, and that a wrathful God avenged by human/divine sacrifice, was still used to excuse violence and war.

Yet despite such a hellish harvest through sowing cultural mores and moral absolutes near and abroad and then claiming persecution when this "holy concern" is resisted—despite this—the I Am did not abandon, does not give up, moves in uncharted terrain, upsets our for’s and against’s, overturns our categories—instead, forgives, hopes and loves.

It was this desire, what might even be called a holy longing—which he could only describe as something like Love’s egg-tooth trying to break through his shell—that he felt warm and growing within.

Years ago this unimportant man awakened to a few things while tying another man’s shoe laces. And although he would cringe at the comparative reference of a mystical seeing such as Julian of Norwich’s, "All will be well, and all manner of things will be well," he may submit to a footnote. To his credit he has not forgotten it all; and to his discredit, he has far too often fallen back asleep. This, in any case, is how he told it to me.

What a great story of transformation. It is always hard to stay awake. Only a special few do. The rest of us are mortal.

Thank you so much Ivon. From a fellow mortal.

Thank you so much for this Stephen. It causes one to pause, rethink, remember, wonder and consider things in a new light.

Thank you Lucy.

Thanks for sharing the “rest of the story,” Steve. So moving …

Thank you Sam.