Years ago, in those foggy days right after my father’s rather sudden death, I was going through some of his old books and I found a scrap of paper upon which he had written a short prayer. It read, "Yes, peace that passes understanding…but give me the understanding that brings peace."

I wondered what he was going through just then. My father sought understanding, searched the epistles for some sense of things; but saw his quandary.

His note referred to Philippians 4.7, where St. Paul speaks of the peace that passes all understanding. But his line was a rebuttal. He was saying, fine, Paul, but I still want the kind of understanding that brings me peace. Dad was grappling with his faith in the middle of tooth and nail circumstance.

My father had many occasions to question his faith, question the faith of his church. And I’m certain now, all these years later, that the questioning ran deeper than any of us suspected. But why would this surprise me? He was, through this little scrap of paper, crying a Psalm…Give me understanding that I may live.

My father had many occasions to question his faith, question the faith of his church. And I’m certain now, all these years later, that the questioning ran deeper than any of us suspected. But why would this surprise me? He was, through this little scrap of paper, crying a Psalm…Give me understanding that I may live.

I remember riding my bicycle home from work after the long distance call from my mother and my brother Paul, informing me that my dad had died of massive heart attack. I stopped on the bank of the North Saskatchewan and sat down in the grass. I’ve always loved rivers and so I just sat there watching the grey-green water flow by. The city sank away. The sun shone warm and the air had a deep-fall fragrance. And in that heavy brilliant afternoon the outline of my father’s smiling face came into view and a the outline of a poem came to mind–a poem that I would later read at my fathers memorial.

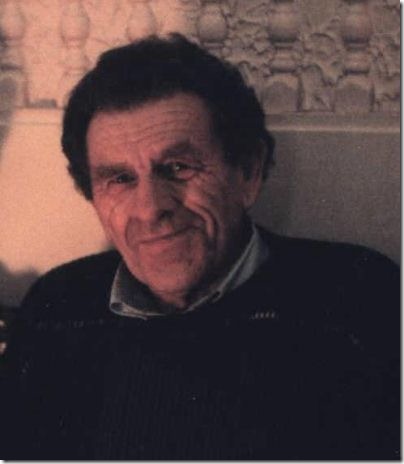

Today, his etched face is still etched in my mind:

I see him sweating, black dirt ground deep in the creases of his wet face. His shirt stuck to his back, rivulets of water running down under his cap, down the side of his face as he shovelled, hammered, lifted, pulled.

I see him crouching, head down, helmet on, while sparks shoot past his arms and legs and  bounce up off the hard-packed dirt of the log tractor shed. He welded a birdbath together using the steel discs of the old seeder. He used farmer–rods, 7014’s. That piece of modern art was eventually anchored in the ground in front of the picture window of the cabin—the cabin he created from the warehouse that was once attached to our store in town, the Springside Shopping Centre.

bounce up off the hard-packed dirt of the log tractor shed. He welded a birdbath together using the steel discs of the old seeder. He used farmer–rods, 7014’s. That piece of modern art was eventually anchored in the ground in front of the picture window of the cabin—the cabin he created from the warehouse that was once attached to our store in town, the Springside Shopping Centre.

In our small living space at the back of the store I see him sitting at the table, beside him a shin-high stack of newspapers and magazines. I hear him, being cynical, and yes, hopeful, about the state of the church, the municipality, the country.

I see him entering the rainfall and weather conditions in that acre of space beside each day on the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool calendar that hung behind his chair.

I hear him tell mom how I was able to pack all the 50 pound bags of flour from the van to the warehouse beside our store. I feel a surge of pride rising through my skinny frame. The struggle had near killed me but in my boyish mind I had averted his disappointment.

I hear him half a mile away in the field, singing above the roar of the 1550 Cockshutt tractor…singing what he always sang in the middle of the field …How Great Thou Art.

In the Baptist Church, I’m noisily fidgeting while Pastor Ulrich preaches and I hear him signal, as he always did, with a long drawn out throat clearing. I face front quick as a consonant, and feel his eyes for a long time on the back of my head.

I hear him laugh mercilessly as he tells the only off-colour joke I’ve ever heard him tell. The one about the farmer who found the whistle in the manure pile. What did he do with it? He blew the shit out of it! All the kids roar. Aunt Nettie and Uncle Harold laugh too, but not as much as dad.

I see his thick wavy black hair sprout from underneath a toque that has climbed up the back of his head while he lays up an even row of snow beside the red Ford half-ton — stuck, on the way to the farm. A farm that raised pigs, hundreds of laying hens, and killed over a thousand turkeys and a farm that compelled dad to be experimental, a general store owner, a public school trustee, a Co-op board president, a bus driver, a Gideon, a deacon…

I see him reading at the table of our other farm–"Jonat’s farm"–the farm we never quite felt at home with. I secretly thank him as he pretends not to notice the scent of tobacco after I come back from smoking a "rollie" behind the bin.

I see him reading at the table of our other farm–"Jonat’s farm"–the farm we never quite felt at home with. I secretly thank him as he pretends not to notice the scent of tobacco after I come back from smoking a "rollie" behind the bin.

I feel his sadness and tension as he drives me to meet friends, friends I’ll leave to the coast with, leaving him behind, not seeing him for several years.

Decades later and two months before his death, I hear the pride in his voice as he recounts the good that all his children did. Kids from small town partner well and make good. Did we recognize ourselves in his rhapsodizing? Dad did.

And one year after his death I dream him in that robins egg blue suit of his, sitting at the dark-wood dinning-room table, and we are all around and we’re laughing.

This is an edited re-post of a personal narrative I wrote several years ago.

My dear friend, Stephen. This is absolutely beautiful. Causes me to think much about my own dad whom we buried in January … an old farmer that, more often than not, was always covered with dirt and sweat. A wonderful tribute on such a day as this.

Thanks so muich Steve – so moving. Tomorrow would have been his 90th birthday!

I remember him telling stories and it sounds like he practiced the Grace-based parenting principles in Dr. Kimmel’s book that I’m reading about with a couple of other families at my church.

Thank you for this. My father, bless him, is still alive (only twenty years my senior!) but I nonetheless have fond memories of him as a young father, constantly busy with building projects, always working with his hands. I appreciate him always…what he taught without knowing it.

David: Thank you so much for your kind encouraging words.

Sam: Thank you, and thanks for the birthday note.

Ian: You’re right about my dad’s grace-based outlook. Some inspiration perhaps as you embark upon your own parenting journey.

Mike: Bless you for your thoughts. It seems to be always the case that we learn best, what isn’t explicitly taught.

Stephen, I met your Dad many years ago when I would visit the Harold Konkel farm. This was the early 1970’s. I was in love with Harold & Nettie Konkel and their strong faith and hard work ethic – and their joy in the midst of all their hardships there on the farm. In Jake I saw the same thing. Thank you for sharing from your heart.

Hi Peggy, Thank you so much for stopping by and introducing yourself. I spent a number of summers at the Konkel’s and have many wonderful memories. Thanks again.