Ours wasn’t a 100-mile diet–it was a 100-yard diet. Our family ate what sprouted from a large patch of tended soil behind our house. What wasn’t eaten straight from the garden was put up in jars and in a root cellar.

And we ate meat. Chickens and pigs mostly, occasionally a young steer or heifer. Sometimes, although rarely, we ate wild meat. Deer or moose—barter with an uncle—as my father didn’t hunt. What we raised and what we didn’t sell, we butchered. Mostly we butchered pigs and chickens. And what we butchered we used.

I didn’t mind the taste of chicken foot soup, it was the thought of the feet. Feet I knew. Feet that’d run through barn-slick mud, feet that scratched up grub-life from beneath the dirt.

Feet I snagged with wire and hook, then held skyward while the chicken, arched-up, caught my sleeve in its beak, and beat my arm and the air with frantic wings. Not effecting its escape it dropped down in a flurry of feathers, breathless and half limp while I pulled it across the stained block and chopped the head free of the neck. Blood splattered on the hard-packed dirt, and the headless chicken flapped its insanity into stillness.

After the blood, after the scalding, the chicken was plucked as it hung with a dozen other chickens from a length of wire stretched between a stall in the barn. After the plucking, after the propane torch singeing to remove the pinfeathers, they were taken to the kitchen for cleaning and cutting. At the end of the day, up in my room, I still caught the smell of chicken entrails as I fell asleep.

When it came time to butcher a pig, a neighbour was called. He placed the gun barrel a few inches away from the forehead of our hog and the bullet entered the brain. Then, strapping hind legs to a block and tackle hung from a protruding beam behind the barn, the pig was pulled up, suspended head-down, its front feet left grazing the ground. My father then eased a bright blade through the soft skin above the breast bone, sticking the carotid artery, and I watched the pig finish twitching and the blood pool like it would never stop. There are pails of blood in a pig.

After the pig was bled it was dipped in a barrel of scalding water then scraped clean of hair and bristle. Finally it was cut from breast bone to pelvis, and opened up, its offal spilling on the ground. The mound was later shovelled on the manure wagon and taken to the field, but not before the cats and our dog were full-gorged.

The carcass cleaned, my father lowered the pigs bulk onto a makeshift sawhorse table and used a meat saw to cut it into manageable chunks, ribs, ham, bacon.

My trip to Sobey’s has none of this drama. And it has none of the understanding or the connection or the remorse. Finally, it has very little of the gratitude. What it does have is emersion in an abundance of cheerful packaging.

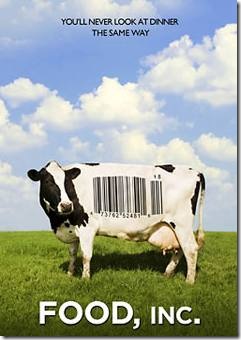

And mostly we believe the propaganda on the packaging—that all is pastoral out in the pasture. In truth, today, chickens are formulated en masse, pigs are machined, cows are designed. Unable to bear the strain of hot-feed and growth hormones, the organs and skeletal structures of these animals are sacrificed in the race for the earliest possible finished product. Any thought for the well-being of the animal has evaporated in the heat of ever expanding production and efficiency, within the demand for cheap fast food—a demand created and sustained both by conglomerates and consumer choice.

And mostly we believe the propaganda on the packaging—that all is pastoral out in the pasture. In truth, today, chickens are formulated en masse, pigs are machined, cows are designed. Unable to bear the strain of hot-feed and growth hormones, the organs and skeletal structures of these animals are sacrificed in the race for the earliest possible finished product. Any thought for the well-being of the animal has evaporated in the heat of ever expanding production and efficiency, within the demand for cheap fast food—a demand created and sustained both by conglomerates and consumer choice.

The disconnection we have to our food has given food conglomerates the power of ancient feudal lords and forced farmers into a new form of serfdom. And our turning away has licensed the engineering of animals over their ethical treatment. But farmer Joel Salatin, in the documentary Food Inc., goes further and says,

A culture that just uses a pig as a pile of protoplasmic inanimate structure, to be manipulated by whatever creative design the human can foist on that critter, will probably view individuals within its community, and other cultures in the community of nations, with the same type of disdain and disrespect and controlling type mentalities.

Joel is one of a growing number of people that see the consequences of our food choices, and our attitude toward food, as an unacknowledged social illness, and part of our communal and spiritual disease. Without a renewed connection to our food through a new heedfulness of the earth and a mindfulness of its plants and animals—that is, without the practice of stewardship, all our supposed productivity is a diminishment of life itself.

But should we take time to reacquaint ourselves with the network of events between our breakfast and its origins, we may regain a sense of our indebtedness—the giftedness of food, in effect, the spirituality of food. And through this, perhaps we may begin to make wiser decisions regarding our food choices—choices that effect the earth we live upon.

I thought this documentary was really well done – not a total-extremist Michael Moore style; although it was provocative and makes you want to flip the bird to the proverbial Man.

Further more, it really hits home to those of us whose parents and grandparents were farmers. The 100 mile diet is certainly not easy for most of us urban dwellers; however, it is certainly a goal we can strive to live by. Sure, Farmers’ Markets may cost a little more but the good of buying local, organic produce outweighs the convenience and cheaper prices of grocery stores. Local produce TASTES far better, you eat what is in season, which is what our bodies need to eat at that time, and it’s a great way to support our local economy.

Thanks for writing about this Steve. Your vivid descriptions of chicken and pig slaughter make me glad I’m a vegetarian. Having said that, I’m of the point of view that as long as an animal lead a life on a free-range farm and was fed the food its body was created to eat, then those of you who eat meat enjoy ? And I mean that with sincerity.

I too am hoping the movie will help us make wiser food choices. Our eagerness to leave our food supply to those promising more for less has enabled the sterilizing, stripping, unethical food supply system we now have. But the truth is that many of us simply don’t have the energy or resources to go out of our way to make truly better food choices, or to affect any substantial change on the system.

And what are wiser food choices? So many have come away from the movie determined to go vegan, and while that may a good choice for some, it is definitely not a good one for others, health-wise, nor is it any more sustainable or green. Most people don’t realize that agriculture, the way we’re doing it, now depends completely on oil, and is not sustainable.

We agree though: gratitude and awareness have mostly disappeared from our relationship with food, and fostering their return is essential if we want to have any hope of putting a stop to factory farming (of both meat and produce) in favour of local small-scale sustainable food production that will both cost more, and deliver more.

Janelle, thanks so much for commenting. I appreciate your open and enlightened position. Not all of us were meant to be vegetarians, but all of us have a responsibility for earth-awareness and good food choices. See you at the Farmer’s Market.

I can see the draw to a vegetarian diet after watching “Food Inc.” But that is a visceral response and not the point of the movie. For me, Joel Salatin, a deversified farmer, raising grass fed cattle, free range chickens etc. was the central figure, and the voice of reason and hope.

You’re absolutely right that impoverished people are often left with “empty” food. Which means there is even more responsibility upon those of us that do have the resources and the energy to make good food choices so that the system begins to reverse. Big systems change very slowly, but Food Inc. did hold out hope for change, and of course, the documentary itself is a catalyst for change.

Thank you for sharing your wisdom Connie!

Thanks for the memories, Steve – the garden, the chickens, pigs and cattle. I remember eating my pet calf – even had a name for him. This has me thinking of the complexities of the global agriculture industry – many inequities and many people to feed.

By the way, you’ll recognize that the cow in the picture is a Holstein, bred for its milk production rather than for its meat, as the bar code on it might suggest.