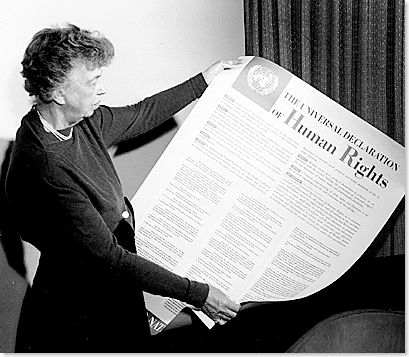

In 1947 when Eleanor Roosevelt convened the first international counsel that would later produce the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it was thought that the implementation of rights would flow from the moral and political force of the document itself. After all, the waste and carnage of two global wars had so wearied the soul of the planet that there was an earnest gut-desire to enter a new era of peace, a "world made new."

Those were heady days. Even as the cold war loomed, there was optimism that the UN, wielding the ethical force of the UDHR–signed by 48 nations, with only 8 abstentions–would be able to convince all nations, even tyrannical nations, to uphold the right to life, liberty and security, of all individuals, regardless of race or religion, colour or creed, political opinion or social origin.

Eleanor would be gravely depressed. The last half of the 20 century has seen countless human rights violations, even by many of the signatories–and especially by the most powerful of signatory. And while over 1000 NGO’s sprung up to monitor human rights implementation, this did little to shame any nation into line.

Today, the Human Rights regime is in apparent crisis. And globalization, instead of drawing us closer, is seemingly splintering nations further. Add to that the current economic pressure and the protectionist bent of every nation and tribe, and the world seems poised for more rounds of violence and human rights abuses.

Does it mean that the UDHR and its attempted application wasn’t worth the effort? Not at all. The UDHR stands as a magna carta of sorts and has no doubt forestalled much entrenched conflict.

But there is a also a core difficulty. If the maintenance of human rights can’t rely on political and moral force what can it rely on? If it relies on physical force it undermines it’s own articles–its own foundation and hope.

So while the declaration is important and needed, it is highly provisional, culturally relative, and forever flawed, because it not only misreads the mimetic nature of violence, but also, because it is "methodologically atheistic." That is, at the point where the UDHR introduces values such as the "innate dignity of humans" it chooses to ground these values in a belief in human moral progress. What I mean is that it tries to stay metaphysically free. But because this is an impossibility it deludes itself and remains tied to the rationality of the Enlightenment, the rationality that lead, in part, to the wars of the 20 century, which then lead to the formation of the UDHR. (For an eloquent and eminently reasoned opposition to my understanding, read Michael Ignatieff’s, Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry.)

So, while the UDHR is still in some way a necessary and humanizing document, it cannot of itself, as was hoped, create a cooperative and peaceful world. Only through a deep understanding of our own propensity for violence, sacrifice and scapegoating, can a trajectory of hope for peace be sustained. As for me, I have found no other narrative other than the gospel, that opens up the possibility of a culture of peace. That’s because it lifts the mask of our innate propensity to first find fault in another.

Close friend just returned from a conference – Phyllis Tickle spoke on discussions sprouting up in the academy on the epistemic eathquakes that happen every 500 years or so in the West….centred on the issue of authority – Greece, Rome, Middle Ages, Renaissance, Enlightenment/Reformation…and rumblings today. I checked out of the Protestant scene 9 years ago. Who’s running the ship? There is such a device as a self-steering mechanism on boats. But it doesn’t work in high seas. Boats that roll break their masts clean off. The real question is, whose hand is on the tiller? …and for God’s sake don’t you dare say ‘Jesus”…

PS…

I love your blogs!

Craig, And I love that you say that.

So we’re due for an epistemic earthquake? Or is it already happening? I do hear the rumblings.

Great blog, Steve. Here are three scattered thoughts in response:

1. Some Christian friends in India, in response to the persecution of Christians by Hindu extremeists have appealed to their state and national governments to uphold their secular constitution which guarantees freedom of religion.

2. I read an article this morning by Norman Geisler – “A premillenial view of law and government” – in which he compares the benefits of a pre- versus a post-millenial view of things to come. He states that premillenialsts have mad three contributions to a peacful society: 1) The belief that only Christ’s return will bring in the Kingdom (in contrast to the posmillenial view that we need to Christianize the world) 2) The belief in religious pluralism, and 3) God’s revelation in nature is the basis for civil government (this would be his answer to your observation about the lack of a basis in ‘methodological atheism” for moal and ethical action)

3. An article in yesterday’s Regina’s Leader-Post in the Religion secion reports on Obama’s address to the National Prayer Breakfast: “… if we can talk to one another openly and honestly, and if perhaps we allow od’s grace to enter into that space that lies between us, then the old rifts will start to mend and new partnerships will begin to emerge. In a world that grows smaller by the day, perhaps we can begin to crowd out the destructive forces of excessive zealotry and make room for the healing power of undrstanding. This is my hope. This is my prayer.” The article also said that Obama “came to Christianity on Chicago’s South Side after college when he worked with ‘church folks’ on community organizing.” (Thought you’d find this last comment interesting, Steve.)

Hey thanks Sam,

1. The constitution of India provides for religious freedom. But I’m wondering about past instances of implementation. Are there any?

2. I disagree with Giesler’s first point. Premillennialism readily slides into an escapist Christianity. He must see that. (Does he consider amillenialism?)

3. Obama is still a breath of fresh air, I still like his vision and his articulation of his vision. But I’m deeply disappointed in his escalation of the the Afgan war. This is not the way to crowd out the forces of zealotry! This is zealotry.