Friday evening was a Cuban reunion of sorts. We four couples (and some friends) who had shared company in Cuba, gathered at the Blue Chair cafe to hear the great Bomba. Three of the six-piece band are from Cuba.  Our friend Philip, who has no social hesitations, soon discovered the details of the Cuban musicians, and would have, if it were possible, invited them back to his place for an extended concert. This is something he successfully accomplished with another band during our stay in Veradero. I listened in as Luis, the leader, explained to Phil how his association with an artists community allowed him leave of Cuba as well as an ability to make return visits. This however, wasn’t the case with the drummer from Matanzas. Such are the mysteries of Cuban emigration.

Our friend Philip, who has no social hesitations, soon discovered the details of the Cuban musicians, and would have, if it were possible, invited them back to his place for an extended concert. This is something he successfully accomplished with another band during our stay in Veradero. I listened in as Luis, the leader, explained to Phil how his association with an artists community allowed him leave of Cuba as well as an ability to make return visits. This however, wasn’t the case with the drummer from Matanzas. Such are the mysteries of Cuban emigration.

I was again reminded of our visit to Cardenas. On that late February day we rode a short ten miles from Veradero to Cardenas to met Oscar, a friend our companions John and Odette had met on a previous visit to Cuba. Our taxi, after its race with a 58ish Pontiac–a race that gave us several life-flashing-in-front-of-our-eyes moments–drove into what John called, “the real Cuba.”

The “real” Cuba is an eviscerated thing. Like the two-days-dead chicken we came across on a sidewalk at the edge of the city, it’s splayed body open to reading. But Cuba is harder to read than chicken entrails.

The checkered entrepreneurial glory of the 20’s–50’s was long gone. But so too were the dreams of a struggle that was to sweep away a corrupt dictatorship and leave a collective, in want of nothing, in its wake.

The checkered entrepreneurial glory of the 20’s–50’s was long gone. But so too were the dreams of a struggle that was to sweep away a corrupt dictatorship and leave a collective, in want of nothing, in its wake.

Today Cuba is one animal with two backs. The increasingly prosperous Cuba, paid for by tours of whites; and the decaying Cuba, haunted by principals of a revolution that looks out from billboards and sides of buildings through the eyes of the two (once) revered revolutionaries. But  those eyes are now full of smoke, the revolutionary symbols, the beret and star, cigar in teeth, the bearded profile, the fatigues, rendered hollow, bereft by the gutted sugar cane factory, the eternally postponed train, and the kneeling and prostrate habitations.

those eyes are now full of smoke, the revolutionary symbols, the beret and star, cigar in teeth, the bearded profile, the fatigues, rendered hollow, bereft by the gutted sugar cane factory, the eternally postponed train, and the kneeling and prostrate habitations.

We walked this prone, prostrate Cuba for an afternoon. Narrow streets, fissured and pock marked, cracked open domiciles slumping on burdened sidewalks. Cinder block and and concrete squares. Blistered paint on the ironwork that covers window holes. And occasional architectural intrigue, as with the stone cathedral–closed to comers.

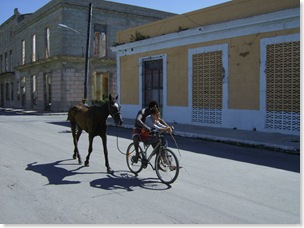

And other sightings and impressions: Clusters of young people sitting on sidewalks, backs to the walls. Old men, selling guava, shouting in the street, lost faith in ideology, a child playing with a 30 foot length of video tape. Two young men playing dominoes on a make-shift table held on their laps. And everywhere, underfed horses pulling carts for passengers–calling them coaches would be an overstatement. And ubiquitous bicycles exceeding load limits–one man balancing a washing machine on what had to be a fortified rear fender.

And other sightings and impressions: Clusters of young people sitting on sidewalks, backs to the walls. Old men, selling guava, shouting in the street, lost faith in ideology, a child playing with a 30 foot length of video tape. Two young men playing dominoes on a make-shift table held on their laps. And everywhere, underfed horses pulling carts for passengers–calling them coaches would be an overstatement. And ubiquitous bicycles exceeding load limits–one man balancing a washing machine on what had to be a fortified rear fender.

Later in the afternoon, Oscar, our new friend and guide, hailed us a buggy and off we went to his house. We clacked along curling pavement, and across  cracked stone intersections. We rode the wrong way on streets designated as one-way, but the traffic rules are suspended, all except the main streets.

cracked stone intersections. We rode the wrong way on streets designated as one-way, but the traffic rules are suspended, all except the main streets.

Upon arriving we met Oscar’s mother, a compact woman who smiled incessantly. We were invited to sit down in the front room and were offered coffee and rum. We talked of family. The neighbour was introduced as Oscar’s second mom. She also smiled constantly. We asked her, through Oscar, about her family. We were told of children, uncles and aunts. The neighbour very much hoped we would come to see her home as well.

Shortly an uncle of Oscar’s arrived. He manoeuvred his bicycle into the small portico and sat down on the edge of a couch. He was wearing a forties suit coat, faded blue baseball cap–permanently fixed–rolled up white slacks and sneakers with toe-holes worn through the canvass. He was 87. We asked about his occupation. He was mechanic and had worked on diesel trains. John asked about his life before the revolution and he pinched his lips and shook his head, as if keeping a lock on stories that could cost things untold. Stories now lost through a controlling, ubiquitous, inexplicable fear.

Shortly an uncle of Oscar’s arrived. He manoeuvred his bicycle into the small portico and sat down on the edge of a couch. He was wearing a forties suit coat, faded blue baseball cap–permanently fixed–rolled up white slacks and sneakers with toe-holes worn through the canvass. He was 87. We asked about his occupation. He was mechanic and had worked on diesel trains. John asked about his life before the revolution and he pinched his lips and shook his head, as if keeping a lock on stories that could cost things untold. Stories now lost through a controlling, ubiquitous, inexplicable fear.

We talked of lighter things… Oscar had helped build his family’s house. A two- story concrete square, comfortable, and by Cardenas’ standards, of a higher stratum. From the front room we toured the kitchen and bathroom and an upstairs with its three small partitions forming bedrooms. A small patio at the rear of the house had a large concrete sink and an enclosure with a pig. We returned from the brief tour and shooed away flies attracted to the sweet rum.

story concrete square, comfortable, and by Cardenas’ standards, of a higher stratum. From the front room we toured the kitchen and bathroom and an upstairs with its three small partitions forming bedrooms. A small patio at the rear of the house had a large concrete sink and an enclosure with a pig. We returned from the brief tour and shooed away flies attracted to the sweet rum.

Oscar had retrieved a cd-player and put on some Latino music. John, and his wife Odette–who never misses a chance to dance–mamboed round the front room. We talked more and smiled at each other, and as guests, aware of a simple charm presiding over our time.

Our friends had brought Oscar gifts. Newspapers, reading material (Oscar loves to study language, and if there is a key to advancement and even emigration, it’s through language.) Also t-shirts, a new pair of Dockers and a CD-Walkman. Every item was passed around. It was Christmas, a birthday…more rum was offered, cigarettes were lit.

Our friends had brought Oscar gifts. Newspapers, reading material (Oscar loves to study language, and if there is a key to advancement and even emigration, it’s through language.) Also t-shirts, a new pair of Dockers and a CD-Walkman. Every item was passed around. It was Christmas, a birthday…more rum was offered, cigarettes were lit.

The father came through and shook hands, silent but smiling, retrieving a smoke and then leaving, to walk or wander. Oscar’s eight year old nephew arrived back from school. Neat and clean in his uniform. Without hesitation or instruction, he offered me his hand. Demure and smiling he moved on, bending forward and in turn kissing Deb and Odette on their cheeks and shaking John’s hand before skipping upstairs to change.

What will become of the light in the nephew eyes? What of Oscar? Of Cardenas? Earlier, while walking the streets by the crumbling factories along the shore, Oscar repeatedly dreamt-out-loud about his hope of leaving Cuba. A grey government migration building, imposing and vacant except for one car in the drive, spoke a death-knell to his hope. But still, despite this desperate longing came the Cuban laugh in all its expansive capacity.

There lives here a gracious horizon of life, perhaps ennobled by threads of hope, woven together. There is an obvious decrepitude on all the surfaces. Yet, from within, the colours of survival, of life and love and breath, shine through at places. All the colours of a vibrant spirit, of life not yet utterly defeated.